The Ring of Memory Qalaya Despite its divine origins The Ring of Memory initially comes across as a simple, if not unassuming band of rough silver inlaid with a stroke of equally course bronze. A crudely crafted piece of jewelry hardly worth more than a few mizas at the market, and certainly not anything astonishing, let alone special enough to warrant a second glance. In fact, even to the magically inclined, the supernatural empowerment bestowed upon the ring is difficult to discern upon first inspection and requires a surprising amount of concentration and scrutiny before one realizes the scope of what it is exactly they are looking at. Whether this curious anonymity for an item of such magnitude was intentional in its original design, an aspect that was added later after the Valterian had left Qalaya more reserved and withdrawn, or simply a by product of its shoddy creation centuries ago still serves to endlessly annoy scholars and historians alike who continue to debate the fact to this day, for there is little that followers of Qalalya abhor more than an unsolved mystery. Yet, one thing is for certain to both the faithful and the otherwise; once adorned upon the wearer’s finger, the full capabilities and sheer significance of the power held within the ring becomes instantly clear. Forged nearly six centuries before the great collapse that sundered empires and reshaped the world, this ring allows the wearer to record a tiny piece of themselves in their writing. Perhaps their voice is recorded in writing so that when read, the wearers voice is heard. If a description of the wearer is written, their ethereal image can be seen. If a book is written about the wearer, they may actually regain some form of immortality through the written word; a manifestation of the wearer powered by the writing in the book as fueled by the magic of the ring. A number of scratches and strange notches can be found all across the ring. While Initially easy to dismiss as the toil of time having left it aged mark on this ancient artifact, upon further inspection it becomes quite clear that the markings were made on purpose. Though meaningless to the current wearer, each scratch and nick in the metal once held great and particular importance to the previous owners who wielded the ring in the past. In ages gone by, wearers would often leave their impression upon the ring if ever they felt they needed to remember a certain moment. By grazing their fingers across said mark, they left an imprint of it that held no significant magical or godly importance, but instead simple acted as a reminder whenever they felt their memory waning. Thanks to the powerful magic coursing through the item however, those that rub the ring today can feel a crude sense of recollection bubbling up beneath each and every scar the ring holds. Though they don’t hold any specifics, a wearer can feel certain vague anamnesis that can often aid them in recalling a similar memory of their own. Forgotten the name of someone who you really shouldn’t have? There’s a little notch on the underside of the ring where Suval of Kadaria left a small hook shaped mark that will help with that. Can’t recall which path you took to get here? Imrahil’s zigzagging scratches across the bronze inlay could be of some aid in helping you find your way back... and so it goes on, each wearer leaving just a bit of themselves behind to aid the next. Origin Secret :

Noteworthy Wielders Secret :

Total Word Count: 3115 |

- Getting Started

- Help

- Master Lists

- Useful Links

- Features

Rings of Power Challenge Weekend (6, 7, 8)

(This is a thread from Mizahar's fantasy role play forums. Why don't you register today? This message is not shown when you are logged in. Come roleplay with us, it's fun!)Feel free to post all your Mizahar related discussions here.

Rings of Power Challenge Weekend (6, 7, 8)

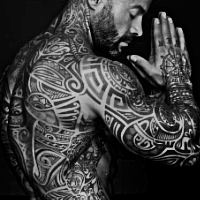

![]() by Elias Caldera on July 9th, 2018, 1:29 am

by Elias Caldera on July 9th, 2018, 1:29 am

-

Elias Caldera - Playa

- Posts: 901

- Words: 1255799

- Joined roleplay: September 14th, 2013, 1:28 am

- Location: Ravok

- Race: Human

- Character sheet

- Storyteller secrets

- Scrapbook

- Journal

- Plotnotes

- Medals: 7

-

-

-

Rings of Power Challenge Weekend (6, 7, 8)

![]() by Quzon on July 9th, 2018, 1:55 am

by Quzon on July 9th, 2018, 1:55 am

Makutsi - Ring of Rivers Guardian

Ring of Rivers Guardian - This ring transforms the wearer into an exceedingly rare, perceived as extinct form of Otani; once child of Laviku, who claims complete allegiance to Makutsi. These Otani, known as Maku after their adoptive mother, serve as guardians over inland bodies of water such as rivers, springs, lakes and oases.

Origin & Creation :

Arnaud Lagrave, known in his later years only as the Drowned Man of Sunberth, was a slave who lived in the mining city during the time of Emperor Kovinus Woniam Nymkarta’s rule over the Alahean Empire. In his time, the government of Sunbeth was supremely fueled by their own individual lusts for power. However, anyone of true influence earned their prosperity on the backs of the slave labor who worked the mines. Arnaud Lagrave was one such person born to be stepped on by the upper echelon of society. Arnaud was a simple man. In fact, he was a short, nervous-looking man with mousy features who only ever wanted to be free of those who opposed him.

Arnaud had rebellious thoughts, but never did much with his life. He was a slave late into the twilight of his life, a slave who could not help but regret how his life had progressed. As he examined his reflection in the waters of the river which ran through Sunberth, Arnaud ran his hand along his receding hairline of silver-gray which spoke of all his hard years of hard labor. His body was well suited for a live of digging through earth, but the wrinkles forming crows feet at the edges of his eyes led him to sob softly to himself after entering into an immense depressive existential crisis.

His pitiful sadness went unnoticed by all save for two people. The first being lurking within the river which watched him the entire time. The second was a slave task master who struck old Arnaud from behind for his inactivity. The blow caused him to fall head first into the water where he never submerged. The miners on duty all reported Arnaud’s death to the mine operators, but Arnaud was actually still alive, whisked away by the a moldling monster in the river.

Arnaud awoke outside of the city bells later on the edge of the river. Arnaud thought he was hallucinating at the sight of a seemingly transparent feminine form looking at him from the water. After all, his mind was still half dazed from the wound on the back of his head where he was struck. As he removed his shirt to bandage the wound, he watched with focused interest as the creature repeatedly transitioned from a feminine to masculine visage.

He spent much of his time with the creature, leaning of the origin of the Maku and its devotion to Makutsi. Arnaud remained in awe of the creature, but wished to know two things. The first was why it seemed to look just as injured as himself. And the second was why did it save him. He was too old do much left with his life, but the Maku cryptically told Arnaud that his will would live on to do great things, and then it completely ignoring the man's first question.

To aid him in surviving his inevitable rise to greatness, the Maku held its arms open as it offered to grant Arnaud some of its power. It was a vague offer, but the former slave had nothing left to lose. The Maku embraced him in a hug, wrapping its arms around his neck where it caress its arm like tendrils along the his head. The Maku then began to exude its immense djed into res, then injected its will through the back of Arnaud's head wound to initiate the ex-slave into the arcane art of reimancy. The Maku waited in curious anticipation once the ritual was completed to see if the human would survive to enjoy its gift.

The initiation into reimancy was an incredibly brutal, yet personal thing. But, it was made all the more unbearable due to the Maku's secret. What it had not told Arnaud was that the Maku had waded through waters plagued with wild djed further up the river. Those impurities were also forced into Arnaud who began to mutate at the wild djed flooding through his body which caused his skin to turn as translucent as a jellyfish. His body took on the aspects of the Maku who had initiated him, which in its own strange way, also caused his body to lose its identity in the same manner as a Morpher.

The Maku was fickle in nature, but enjoyed watching its new plaything as Arnaud tried to understand his new form after having become a Maku-shifter. Within a year of his transformation, Arnaud had practically become a Maku himself; spending most days singing with others, protecting the river of Sunberth where he slowly began to lose track of his sanity from intense amount of daily overgiving. He mastered the transition, then returned to make a name for himself in Sunberth.

The city of Sunberth slowly began to fear ‘The Drowned Man’; a hooded man who would pull people he didn't like into the river. Many would watch as the Drowned Mans body would simply vanish; him becoming fluid as a Maku. And vanish, leaving only the victim struggling to resurface until they finally returned as a drowned corpse. Arnaud became a monster to the city, but became a defender of the river to terrorize those who saw fit to traverse the riverways without giving Makutsi her due praise. And even still, his grudge against the slave masters who ran the mines still lingered.

On multiple occasions, Arnaud led many of the mine Overseers to their death. This became such a persistent problem that the governing Wizard of Sunberth was forced to take a vested interest in the actions of this 'Drowned Man'.

Ivander Grain, known as the then ruling Wizard of Sunberth, was also one of the premiere arcane master crafters and lead animatior who aided, oversaw, and constructed many of the advanced golems which aided in the day-to-day operations and control of the mines.

He knew that all disruptions to the flow of treasures being shipped along the river from the mine shafts furthest from the city would mean a loss of treasure use to support Emperor Kovinus’s war efforts against the Suvan. While many of the Wizards who ran the city hated Kovinus for inciting false hope within the slave populous by removing many of the Wizards best privileges that came with their status, the Wizards responded by ruling rightfully over their slaves with a tighter iron fist.

Ivander's plan was simple, catch the Drowned man by being a harsh task master near the river. He studied The Drowned Man's method of operation, which ultimately led to his success. Arnaud tried to assault Ivander, but quickly found that the man was protected by arcane shielding from most of his attacks. In the end, the Drowned Man was slain by a vast multitude advanced humanoid golems designed specifically to protect the Wizard Ivander.

Ivander took Arnaud's remains to study them to understand how a man had become an Otani. As a result, Arnaud's death gave him insight into the ways of the sub-Otani known as the Maku. And in its own twisted way, the Maku who had empowered Arnaud was correct in saying "his will would live on". Ivander ordered that several shines to Makutsi be built along every bridge across the rivers of Sunberth to honor the goddess. It was an act which seemed to calm any Maku in the area, and even after Ivander used Malediction to craft Arnaud's skull into a ring a of morbid beauty.

The band of the ring was made up of a carved and hollowed out section of Arnaud’s femur, and the jewelry held in place by gold plated section of his skull, remains a shinned area of the front of his skull. Makutsi herself had been watching Arnaud with the unknowable curiosity of a god, she saw fit to bless appear before Ivander to bless the Ring of Rivers Guardian, which left the ring with a shimmering blue hue as if looking at the surface of a lake. When Ivander died he passed it onto the next ruling wizard of Sunberth who died during the Valterrian, which oddly enough, at the time they stood on the edge of the river of Sunberth to which the ring fell into when the successor's body was vaporized by the blast.

Arnaud had rebellious thoughts, but never did much with his life. He was a slave late into the twilight of his life, a slave who could not help but regret how his life had progressed. As he examined his reflection in the waters of the river which ran through Sunberth, Arnaud ran his hand along his receding hairline of silver-gray which spoke of all his hard years of hard labor. His body was well suited for a live of digging through earth, but the wrinkles forming crows feet at the edges of his eyes led him to sob softly to himself after entering into an immense depressive existential crisis.

His pitiful sadness went unnoticed by all save for two people. The first being lurking within the river which watched him the entire time. The second was a slave task master who struck old Arnaud from behind for his inactivity. The blow caused him to fall head first into the water where he never submerged. The miners on duty all reported Arnaud’s death to the mine operators, but Arnaud was actually still alive, whisked away by the a moldling monster in the river.

Arnaud awoke outside of the city bells later on the edge of the river. Arnaud thought he was hallucinating at the sight of a seemingly transparent feminine form looking at him from the water. After all, his mind was still half dazed from the wound on the back of his head where he was struck. As he removed his shirt to bandage the wound, he watched with focused interest as the creature repeatedly transitioned from a feminine to masculine visage.

He spent much of his time with the creature, leaning of the origin of the Maku and its devotion to Makutsi. Arnaud remained in awe of the creature, but wished to know two things. The first was why it seemed to look just as injured as himself. And the second was why did it save him. He was too old do much left with his life, but the Maku cryptically told Arnaud that his will would live on to do great things, and then it completely ignoring the man's first question.

To aid him in surviving his inevitable rise to greatness, the Maku held its arms open as it offered to grant Arnaud some of its power. It was a vague offer, but the former slave had nothing left to lose. The Maku embraced him in a hug, wrapping its arms around his neck where it caress its arm like tendrils along the his head. The Maku then began to exude its immense djed into res, then injected its will through the back of Arnaud's head wound to initiate the ex-slave into the arcane art of reimancy. The Maku waited in curious anticipation once the ritual was completed to see if the human would survive to enjoy its gift.

The initiation into reimancy was an incredibly brutal, yet personal thing. But, it was made all the more unbearable due to the Maku's secret. What it had not told Arnaud was that the Maku had waded through waters plagued with wild djed further up the river. Those impurities were also forced into Arnaud who began to mutate at the wild djed flooding through his body which caused his skin to turn as translucent as a jellyfish. His body took on the aspects of the Maku who had initiated him, which in its own strange way, also caused his body to lose its identity in the same manner as a Morpher.

The Maku was fickle in nature, but enjoyed watching its new plaything as Arnaud tried to understand his new form after having become a Maku-shifter. Within a year of his transformation, Arnaud had practically become a Maku himself; spending most days singing with others, protecting the river of Sunberth where he slowly began to lose track of his sanity from intense amount of daily overgiving. He mastered the transition, then returned to make a name for himself in Sunberth.

The city of Sunberth slowly began to fear ‘The Drowned Man’; a hooded man who would pull people he didn't like into the river. Many would watch as the Drowned Mans body would simply vanish; him becoming fluid as a Maku. And vanish, leaving only the victim struggling to resurface until they finally returned as a drowned corpse. Arnaud became a monster to the city, but became a defender of the river to terrorize those who saw fit to traverse the riverways without giving Makutsi her due praise. And even still, his grudge against the slave masters who ran the mines still lingered.

On multiple occasions, Arnaud led many of the mine Overseers to their death. This became such a persistent problem that the governing Wizard of Sunberth was forced to take a vested interest in the actions of this 'Drowned Man'.

Ivander Grain, known as the then ruling Wizard of Sunberth, was also one of the premiere arcane master crafters and lead animatior who aided, oversaw, and constructed many of the advanced golems which aided in the day-to-day operations and control of the mines.

He knew that all disruptions to the flow of treasures being shipped along the river from the mine shafts furthest from the city would mean a loss of treasure use to support Emperor Kovinus’s war efforts against the Suvan. While many of the Wizards who ran the city hated Kovinus for inciting false hope within the slave populous by removing many of the Wizards best privileges that came with their status, the Wizards responded by ruling rightfully over their slaves with a tighter iron fist.

Ivander's plan was simple, catch the Drowned man by being a harsh task master near the river. He studied The Drowned Man's method of operation, which ultimately led to his success. Arnaud tried to assault Ivander, but quickly found that the man was protected by arcane shielding from most of his attacks. In the end, the Drowned Man was slain by a vast multitude advanced humanoid golems designed specifically to protect the Wizard Ivander.

Ivander took Arnaud's remains to study them to understand how a man had become an Otani. As a result, Arnaud's death gave him insight into the ways of the sub-Otani known as the Maku. And in its own twisted way, the Maku who had empowered Arnaud was correct in saying "his will would live on". Ivander ordered that several shines to Makutsi be built along every bridge across the rivers of Sunberth to honor the goddess. It was an act which seemed to calm any Maku in the area, and even after Ivander used Malediction to craft Arnaud's skull into a ring a of morbid beauty.

The band of the ring was made up of a carved and hollowed out section of Arnaud’s femur, and the jewelry held in place by gold plated section of his skull, remains a shinned area of the front of his skull. Makutsi herself had been watching Arnaud with the unknowable curiosity of a god, she saw fit to bless appear before Ivander to bless the Ring of Rivers Guardian, which left the ring with a shimmering blue hue as if looking at the surface of a lake. When Ivander died he passed it onto the next ruling wizard of Sunberth who died during the Valterrian, which oddly enough, at the time they stood on the edge of the river of Sunberth to which the ring fell into when the successor's body was vaporized by the blast.

Second Owner :

Uhaga The Slitted Throat was a Myrian male, born in Taloba was one of the first to leave the city to explore far off land post-Valterrian. In the years of his youth, he was considered the most talented scout to many Dhani war efforts in the Taloban army and was often asked to stay out in the wilderness which gifted him the skill necessary to take on the harsh personal endeavor of exploration in his adult years. He was also a affluent dancer in is free time. When ever there was a celebration, he would be the first to start dancing around the fire.

When Makutsi heralded her arrived a day before he chose to set off on his adventure, he joined with the many raindancers to honor her name. Makutsi had long since rescued her blessed ring, and saw fit to gift it to one of the dancers that day. Uhaga was shocked to learn that the goddess enjoyed his dancing and decided to dance with him as he turned into a Maku during the Rain Festival. She touched him on the shoulder, and from then on his was marked by her as a Raindancer.

Uhaga had already served his mandatory years of service in the military, so was set to wander off on his own adventures to make way before returning home. However, was asked to rejoin the military by many who saw his gift as a tactical advantage over the Dhani and even those beings who invaded from the water known as Charoda. Uhaga was a free spirited person who's thoughts of adventure and exploration were far more progressive than any other Myrian at the time, but he was also a proud Myrian warrior. The call for battle dulled his thoughts of exploration, if only for a few years longer.

His greatest deed was one of an undaunted defender; with no expectation of survival, he along with a fang of three other myrians kept a foothold at the Kandukta Basin after being beset upon by thirty Dhani in a surprise ambush. He used his ability to shift into a Maku to defeat many of his opponents by using the lake to his advantage until reinforcements arrived.

It was an awesome sight to behold by his allies when Uhaga's watery form shifted in size, growing his upper body as large as that of a whale with his lower body under the surface of the lake. His lashed out wildly in all directions, reaching out like watery tendrils of a giant squid at his foes. The Dhani were instantly caught off guard by the Maku who suddenly decided to drown any snake it could capture in the lake, even worse, launching hash jet streams of water reimancy at them. The skirmish ended with Uhaga The Slitted Throat being hailed as one of the few male Myrian heroes of his age. While he never did live to ever explore beyond the borders of Falyndar, he joined Myri's Shadow guard in his afterlife once he died of old age. The Ring of Rivers Guardian was then returned to Makutsi by Myri herself.

When Makutsi heralded her arrived a day before he chose to set off on his adventure, he joined with the many raindancers to honor her name. Makutsi had long since rescued her blessed ring, and saw fit to gift it to one of the dancers that day. Uhaga was shocked to learn that the goddess enjoyed his dancing and decided to dance with him as he turned into a Maku during the Rain Festival. She touched him on the shoulder, and from then on his was marked by her as a Raindancer.

Uhaga had already served his mandatory years of service in the military, so was set to wander off on his own adventures to make way before returning home. However, was asked to rejoin the military by many who saw his gift as a tactical advantage over the Dhani and even those beings who invaded from the water known as Charoda. Uhaga was a free spirited person who's thoughts of adventure and exploration were far more progressive than any other Myrian at the time, but he was also a proud Myrian warrior. The call for battle dulled his thoughts of exploration, if only for a few years longer.

His greatest deed was one of an undaunted defender; with no expectation of survival, he along with a fang of three other myrians kept a foothold at the Kandukta Basin after being beset upon by thirty Dhani in a surprise ambush. He used his ability to shift into a Maku to defeat many of his opponents by using the lake to his advantage until reinforcements arrived.

It was an awesome sight to behold by his allies when Uhaga's watery form shifted in size, growing his upper body as large as that of a whale with his lower body under the surface of the lake. His lashed out wildly in all directions, reaching out like watery tendrils of a giant squid at his foes. The Dhani were instantly caught off guard by the Maku who suddenly decided to drown any snake it could capture in the lake, even worse, launching hash jet streams of water reimancy at them. The skirmish ended with Uhaga The Slitted Throat being hailed as one of the few male Myrian heroes of his age. While he never did live to ever explore beyond the borders of Falyndar, he joined Myri's Shadow guard in his afterlife once he died of old age. The Ring of Rivers Guardian was then returned to Makutsi by Myri herself.

Last Known User :

Kal Metrini, High Priest of Makutsi's Tower is an earnest man. He spent a vast majority of his life devoted to the river goddess, a peaceful man of the river. It was why he was marked as a Raindancer. Makutsi does not offer her boon to those who are undeserving or lack devotion. She takes pride in knowing that her worshipers would utilize her divine nature with care. That was why she gifted Kal her ring prior to him obtaining his third mark. He was a man who simply wished to dance as he worshiped, but she tasked him to a quest that would require him to enter combat.

She tasked him with destroying the seedheart of a Vinumia stifling the flow of water through the Bluevein as it crafted a multitude of dam like structures to protect its heart. He accepted the quest happily, but knew it was far beyond his skills to preform. That was why he called on the Akalak to aid him in his task. It hardly surprised him when several groups of warriors volunteered to join him.

The journey along the Bluevein went as fast as travel could be when traversing the Sea of Grass. Kal followed the low flowing river until he and his party came upon an unusual sight. The first damn they came across had of a multitude of dead bodies tightly sown together within the patchwork of vegetation. It took them several bells to remove the dam, but as they progressed onward, the kept running into similar blockages. After the fourth dam was destroyed, the river seemed to flow as normal, which Kal was happy to see but it was not his task. There was no sign of a Vinumia. They pressed on for a day before camping for the night.

The night was going as normal when the Akalak on watch let out a deep scream in agony. Kal woke up in a start, hurrying out of his tent to find the camp being attacked by a group of strangely monstrous creatures. Each of them were different in some way. One had horns where another had insect-like antenna, others had elongated noses like beaks where others had snouts of a pig. Kal glanced around as an Akalak yelled out "Wretched Ones". Kal quickly wondered why those who served Uldr would try to halt the river, but then quickly found the answer from his own question. Those who serve the god of undead simply want everything to die, even rivers.

The Akalak were proving to be an equal match for the invaders, but they had a titan on there side. From behind them, attacking any one it could with wild abandon, came the raging Vinumia from river.

Kal knew what he needed to do from that moment. He ran his thumb along the ring as he focused on his transformation into a Maku which shifted his body seamlessly into its humanoid state as he went to confront it at the shore of the river where he quickly ran into the water. The monster lashed out with a vine, aiming to stab him through the gut, but it simply pieced his liquid body, causing him to revert into a fluid back into the river.

The landspawn believed it had destroyed its prey, causing it to turn its attention onto the ensuing battle at the campsite. Kal reformed as he resurfaced from the water, and lashed out in a similar way the Vinumia did but with a long blast of water that cut through some of the creatures vines from the pressure the water exerted. The beast lashed out with another vine of its own, but found the vine quickly decapitated from the uses of water reimancy.

A creature that was hard pressed to be beaten in water, had met a like minded foe in Kal so long as he had the ring gifted to him by his goddess. Several Akalak had joined him once they had slain their foes, failing to keep one as a prisoner as the last foe committed Suicide rather than be captured. Many of the others had also perished, but Kal was glad his party were the victors. They stood at range, primed to fire at the creatures seedheart as Kal shredded away its protective shell of vegetation.

It came down to a battle of inches as Kal traded blows that would have felled a normal man. He used his arms to reach out and pull its body closer to the water, but the beast proved smart enough to know that it would fair better on land against the Maku if it wanted to survive. Kal threatened it repeatedly with the danger of being in water when he felt it was far to focused on trying to strike at him.

He let go of whatever group of vines his watery arms could grab, then fired a blast of water at it gut which managed expose the seed heart in its belly. “Fire” Kal yelled, signaling for the Akalak to fire a volleys of crossbows bolts at it gut. Most of the bolts managed to hit their mark which only proved to stun the monster for just the fraction of a tick. It was in that moment when Kal musted up all the power the ring granted him, then launched a water bolt with immense concussive force at the exposed seedheart, yelling in excitement as the water bolt shattered it like a sledgehammer bashing into a glass trinket, and exploding out the backside of the Vinumia’s torso.

Kal had finished his task and understood how strong the ring of power was that the goddess of the River had bestowed to him. He returned to Makutsi's Tower, contemplating the ring the entier way back to Riverfall. He was a humble man, one that did not wish to use the Goddess power for selfish or petty reasons such as violence. He transformed into the Maku form one last time, just to know how it felt before reverting to his his human form again, then removed it to holding it out towards empty air. He prayed in silence. “I can not keep this.” He said, but before as he opened his eyes from praying, Makutsi stood across from him with her hands clapped around his where he held it. She then blessed him with his third mark, telling her new priest to guard it and use it wisely.

The ring is now guarded by Kal Metrini in the city of Riverfall at Makutsi's Tower. Although a rare site to behold, he often uses the Maku form the ring grants him when preforming his version a rain dance.

She tasked him with destroying the seedheart of a Vinumia stifling the flow of water through the Bluevein as it crafted a multitude of dam like structures to protect its heart. He accepted the quest happily, but knew it was far beyond his skills to preform. That was why he called on the Akalak to aid him in his task. It hardly surprised him when several groups of warriors volunteered to join him.

The journey along the Bluevein went as fast as travel could be when traversing the Sea of Grass. Kal followed the low flowing river until he and his party came upon an unusual sight. The first damn they came across had of a multitude of dead bodies tightly sown together within the patchwork of vegetation. It took them several bells to remove the dam, but as they progressed onward, the kept running into similar blockages. After the fourth dam was destroyed, the river seemed to flow as normal, which Kal was happy to see but it was not his task. There was no sign of a Vinumia. They pressed on for a day before camping for the night.

The night was going as normal when the Akalak on watch let out a deep scream in agony. Kal woke up in a start, hurrying out of his tent to find the camp being attacked by a group of strangely monstrous creatures. Each of them were different in some way. One had horns where another had insect-like antenna, others had elongated noses like beaks where others had snouts of a pig. Kal glanced around as an Akalak yelled out "Wretched Ones". Kal quickly wondered why those who served Uldr would try to halt the river, but then quickly found the answer from his own question. Those who serve the god of undead simply want everything to die, even rivers.

The Akalak were proving to be an equal match for the invaders, but they had a titan on there side. From behind them, attacking any one it could with wild abandon, came the raging Vinumia from river.

Kal knew what he needed to do from that moment. He ran his thumb along the ring as he focused on his transformation into a Maku which shifted his body seamlessly into its humanoid state as he went to confront it at the shore of the river where he quickly ran into the water. The monster lashed out with a vine, aiming to stab him through the gut, but it simply pieced his liquid body, causing him to revert into a fluid back into the river.

The landspawn believed it had destroyed its prey, causing it to turn its attention onto the ensuing battle at the campsite. Kal reformed as he resurfaced from the water, and lashed out in a similar way the Vinumia did but with a long blast of water that cut through some of the creatures vines from the pressure the water exerted. The beast lashed out with another vine of its own, but found the vine quickly decapitated from the uses of water reimancy.

A creature that was hard pressed to be beaten in water, had met a like minded foe in Kal so long as he had the ring gifted to him by his goddess. Several Akalak had joined him once they had slain their foes, failing to keep one as a prisoner as the last foe committed Suicide rather than be captured. Many of the others had also perished, but Kal was glad his party were the victors. They stood at range, primed to fire at the creatures seedheart as Kal shredded away its protective shell of vegetation.

It came down to a battle of inches as Kal traded blows that would have felled a normal man. He used his arms to reach out and pull its body closer to the water, but the beast proved smart enough to know that it would fair better on land against the Maku if it wanted to survive. Kal threatened it repeatedly with the danger of being in water when he felt it was far to focused on trying to strike at him.

He let go of whatever group of vines his watery arms could grab, then fired a blast of water at it gut which managed expose the seed heart in its belly. “Fire” Kal yelled, signaling for the Akalak to fire a volleys of crossbows bolts at it gut. Most of the bolts managed to hit their mark which only proved to stun the monster for just the fraction of a tick. It was in that moment when Kal musted up all the power the ring granted him, then launched a water bolt with immense concussive force at the exposed seedheart, yelling in excitement as the water bolt shattered it like a sledgehammer bashing into a glass trinket, and exploding out the backside of the Vinumia’s torso.

Kal had finished his task and understood how strong the ring of power was that the goddess of the River had bestowed to him. He returned to Makutsi's Tower, contemplating the ring the entier way back to Riverfall. He was a humble man, one that did not wish to use the Goddess power for selfish or petty reasons such as violence. He transformed into the Maku form one last time, just to know how it felt before reverting to his his human form again, then removed it to holding it out towards empty air. He prayed in silence. “I can not keep this.” He said, but before as he opened his eyes from praying, Makutsi stood across from him with her hands clapped around his where he held it. She then blessed him with his third mark, telling her new priest to guard it and use it wisely.

The ring is now guarded by Kal Metrini in the city of Riverfall at Makutsi's Tower. Although a rare site to behold, he often uses the Maku form the ring grants him when preforming his version a rain dance.

- Words: 3003

Last edited by Quzon on March 12th, 2019, 10:55 pm, edited 1 time in total.

-

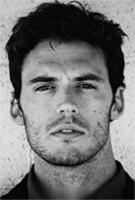

Quzon - Victory & Power

- Posts: 318

- Words: 272095

- Joined roleplay: August 20th, 2013, 11:30 pm

- Location: Syka

- Race: Mixed blood

- Character sheet

- Storyteller secrets

- Plotnotes

- Medals: 1

-

Rings of Power Challenge Weekend (6, 7, 8)

![]() by Kelski on July 9th, 2018, 2:53 am

by Kelski on July 9th, 2018, 2:53 am

Akvin's Ring Of Power: 3257 words

Abstract:

The Ring Of Creation

The Story:

How The Ring Of Creation Came To Be

Whereabouts:

The Current Location & Ringbearer

Abstract:

The Ring Of Creation

Secret :

In approximately 250 A.V. Tylin Dyres lead his entire people including every man woman and child to the surface after their ancestors took shelter in the bowls of the earth to escape the wicked and fatal Djed Storms that resulted from The Valterrian. That migration included several Gods, Goddesses and Godlings that had been passing time with The Dyres family, assisting them in their subterranean survival.

Having been born beneath the surface and finding life above a challenge, these people were at a distinct disadvantage in relocating from the dark confines of the earth to the surface. The Dyres and their people made the move, however, because it was quite clear to them that in order to thrive and expand, they would have to have more space and more opportunities than life within the earth afforded them.

However, born below they were lacking in almost all the major skills and information needed to survive above.

Because of this huge gap in knowledge, Gods, Goddesses and Godlings crafted items of wonderous power to assist their pet humans with survival in the open air and to give them a fighting chance in the first few years of what then was called The Surfacing. Akvin and his contribution was just one of many gifts offered humanity as the elder race.

Akvin’s gift to the world was The Ring of Creation. This beautifully crafted ring allowed the wearer, when faced with a problem that cannot be solved (because no knowledge existed on how to solve it), to instantaneously craft a simple mundane item or part to help solve the problem. A great deal of the population of the world had perished in Ivak’s wrath, and almost all of the known and written knowledge of surface living perished with these dead. They truthfully had no way to rediscover it without a great deal of trial and error, experimentation, and life-threatening delays.

The Dyres had to feed themselves. They had to clothe themselves. And the methods below ground simply would not translate to the surface where the air was fresh, there was room to breathe, and there was hope that the bloodlines of multiple pockets of survivors could be mingled for increased health.

The number one problem of the people surfacing was that they didn’t know WHAT they needed to accomplish important tasks (such as growing food) out in the open air that they had done beneath the surface. Whole generations were born in the dark. This lack of light resulted in knowledge sets and toolkits in mental and physical inventory of these people that were rarely cross compatible with surface living.

Farming, for example, was far different than the aquaponics that they had utilized beneath the surface to keep themselves fed. The laboring and failing machinations of the Pre-Valterrian world simply had to be replaced by modernization or the other sources of food, water, and shelter. People had grown crowded, interbred, and less physically suited to being able to climb out of their holes and live as the Gods meant people to live… under Syna’s light.

Akvin couldn’t be everywhere at once even though he had a true investment in wanting to see Dyres and his family succeed. This investment was simple friendship. Treated as a member of their family, Akvin had long been welcomed among The Dyres and had found common ground with the family and their dependents.

That being the case, he offered Tylin Dyres an incredible life-altering gift. The Ring of Creation replaced a great deal of knowledge the Dyres family and their people lacked. When Akvin and his immortal cohort weren’t around, then ring was able to fill in gaps in the knowledge people had. Tools materialized at the wearer’s need to assist their day to day lives that none of the below ground dwellers had ever seen before. Clever blacksmiths and other sorts of craftsmen were able to duplicate these briefly manifesting items and thus things like the first plows were created.

These creations lasted a single day before turning to dust. Nothing huge or complicated ever manifested. Life on the surface was reduced to simple day to day survival so the items that indeed appeared were often the simplest of things. They were limited in scope and size to the mass of the wearer or somewhat smaller. The concept was such a simple thing, but these quickly manifested items were often enough to pass along the knowledge Akvin retained from the Pre-Valterrian world onto the newly born world of The Post Valterrian era.

And because of the Ring of Creation, Dyres and his family and all their people survived long enough to lay the first stones to the fortress of Syliras. It was a very close thing that the entire region became Sylira rather than Kultra, for both Gods had an equal and important part in humanities survive in that region. It just so happened Sylir died and thus the region was honored with his name rather than Kultra’s.

Having been born beneath the surface and finding life above a challenge, these people were at a distinct disadvantage in relocating from the dark confines of the earth to the surface. The Dyres and their people made the move, however, because it was quite clear to them that in order to thrive and expand, they would have to have more space and more opportunities than life within the earth afforded them.

However, born below they were lacking in almost all the major skills and information needed to survive above.

Because of this huge gap in knowledge, Gods, Goddesses and Godlings crafted items of wonderous power to assist their pet humans with survival in the open air and to give them a fighting chance in the first few years of what then was called The Surfacing. Akvin and his contribution was just one of many gifts offered humanity as the elder race.

Akvin’s gift to the world was The Ring of Creation. This beautifully crafted ring allowed the wearer, when faced with a problem that cannot be solved (because no knowledge existed on how to solve it), to instantaneously craft a simple mundane item or part to help solve the problem. A great deal of the population of the world had perished in Ivak’s wrath, and almost all of the known and written knowledge of surface living perished with these dead. They truthfully had no way to rediscover it without a great deal of trial and error, experimentation, and life-threatening delays.

The Dyres had to feed themselves. They had to clothe themselves. And the methods below ground simply would not translate to the surface where the air was fresh, there was room to breathe, and there was hope that the bloodlines of multiple pockets of survivors could be mingled for increased health.

The number one problem of the people surfacing was that they didn’t know WHAT they needed to accomplish important tasks (such as growing food) out in the open air that they had done beneath the surface. Whole generations were born in the dark. This lack of light resulted in knowledge sets and toolkits in mental and physical inventory of these people that were rarely cross compatible with surface living.

Farming, for example, was far different than the aquaponics that they had utilized beneath the surface to keep themselves fed. The laboring and failing machinations of the Pre-Valterrian world simply had to be replaced by modernization or the other sources of food, water, and shelter. People had grown crowded, interbred, and less physically suited to being able to climb out of their holes and live as the Gods meant people to live… under Syna’s light.

Akvin couldn’t be everywhere at once even though he had a true investment in wanting to see Dyres and his family succeed. This investment was simple friendship. Treated as a member of their family, Akvin had long been welcomed among The Dyres and had found common ground with the family and their dependents.

That being the case, he offered Tylin Dyres an incredible life-altering gift. The Ring of Creation replaced a great deal of knowledge the Dyres family and their people lacked. When Akvin and his immortal cohort weren’t around, then ring was able to fill in gaps in the knowledge people had. Tools materialized at the wearer’s need to assist their day to day lives that none of the below ground dwellers had ever seen before. Clever blacksmiths and other sorts of craftsmen were able to duplicate these briefly manifesting items and thus things like the first plows were created.

These creations lasted a single day before turning to dust. Nothing huge or complicated ever manifested. Life on the surface was reduced to simple day to day survival so the items that indeed appeared were often the simplest of things. They were limited in scope and size to the mass of the wearer or somewhat smaller. The concept was such a simple thing, but these quickly manifested items were often enough to pass along the knowledge Akvin retained from the Pre-Valterrian world onto the newly born world of The Post Valterrian era.

And because of the Ring of Creation, Dyres and his family and all their people survived long enough to lay the first stones to the fortress of Syliras. It was a very close thing that the entire region became Sylira rather than Kultra, for both Gods had an equal and important part in humanities survive in that region. It just so happened Sylir died and thus the region was honored with his name rather than Kultra’s.

The Story:

How The Ring Of Creation Came To Be

Secret :

Gods are fickle creatures. Their attentions can be all over the place ranging from fleeting to obsessive and anywhere in between. And because their lives have no set course as mortals do, they do not acutely feel the movement of time like a human might sense his or her encroaching death with the passing of years. Instead, those that rule Mizahar go out into the world, masquerading as all sorts of things, in order to fill their days with more than just endless sunrises and sunsets.

Akvin Kultra was one such creature. The creative, innovative master inventor was passing time hanging with the riff raff off the coast of the new sea far beneath the surface. Ivak destroyed the world five centuries before and humanity was just now on the cusp of emerging like a grub from the soil they’d taken shelter in.

They had started small, sending adventurous types up and out onto the surface to explore and report. Later, hunting parties had gone forth and while some never returned, enough did with fresh meat and wild edibles that people started growing restless. The signs of Djed Storms had long been gone, though their memory still terrified the huddled masses. And so it was the leadership of the humans of the Dyres family gathered, made plans, and came to agree that it was time to at least partially surface.

“Are you sure it’s safe?” Tylin Dyres asked again, raising an eyebrow and glancing at Glav. The three of them were yet again having a meeting. Akvin was growing weary of meetings. He required action rather than the talk of action, so his leather clad knee was bouncing restlessly much like a deviant child. Glav gave him a look that included a raised eyebrow and the miscreant God shrugged. Unlike Glav, Akvin had his doubts these humans could survive the surface.

He wanted them too.

However, they simply had forgotten so much in their day to day living. His doubt was the reason Tylin was asking Glav and not Akvin. Akvin would have told him straight that he felt humanity to newly stupid to survive the surface since Ivak had robbed them of all their culture and hard-won advances in technology. Had more written work survived, then Humans would have had a fighting chance to make it on the surface. However, as things were saying Humans could survive was like trying to tell a person they could learn to cook without pots, pans, ingredients, recipes or even a fire.

Akvin knew it. Glav knew it. By Sylir’s pristine yet very dead balls, even The Goddess of Memory and Writing knew it. Akvin grumbled. He gave Glav a seething look. The son of Sylir hadn’t yet rose to replace Peace and probably couldn’t for some time to come. Certain things would have to happen first, namely Xhyvas making an appearance back to the land of living in order for them to pinpoint where they could rob enough divine to raise Glav’s power to that of Sylir’s former glory.

Until then, they would have to bide their time. Glav just chuckled at Akvin’s seething glance. He knew Akvin was restless and wanted to get the migration upwards underway, but he also knew that he didn’t want it to be an outright slaughter when the humans beneath faced the wildlife above.

“Its not going to be safe for a long long time. But if you are asking have the Djed Storms passed, yes… unless something else significant changes above, the abnormal weather has settled and you shouldn’t be facing those issues when you surface.” Glav assured him, knowing it to be true. He himself had consulted with Zulrav and the God of the Winds had indeed assured him that the wild djed had spent itself enough to stop effecting the weather and creating abnormal storms.

Tylin Dyres nodded, looked thoughtful, and sighed. “We’ll plan the ascent for the first of Spring. I can’t think of a better way to celebrate one more year of survival than to do it on the anniversary of The Valterrian.” He said thoughtfully. “Then we can see if we can get fields going, crops planted, and perhaps break ground on some sort of stronghold.” He said, tapping his chin and glancing around at his advisors.

Glav and Akvin nodded, though Glav was the only one truly focused on Tylin’s words. Akvin’s head was already miles away. He’d had an idea, and one that would require him to look up Qalaya’s location and ask a boon of Her. Akvin was a player who knew how to stack the decks. He was going to see if he couldn’t indeed ‘stack the deck’ for Tylin and his people before the deadline the human leader had just set for himself.

That meant finding Qalaya. Akvin glanced at Glav. When the others at the meeting were distracted with the business at hand and discussing things loudly, the Magecrafter leaned over and asked Glav a question. “Do you have any idea where Qalaya is? I just had an idea for something that might help Tylin and I need something from Her to do it.” He said, looking thoughtful. Glav shrugged. “She could be anywhere. Last I heard She was …. “ He seemed to reach inside himself, as if struggling for the memory. “Lormar Tower.” He said abruptly. “There were already surfaced mages there with a remnant library she was collecting.” Glav elaborated.

Akvin nodded. Glav had an excellent memory and an ear on the chatter the Gods carried out among themselves. If anyone knew where she was last seen, it would have been him. “Think shes still there?” He asked casually, already planning a trip.

Glav nodded. “I don’t see why not. She’s probably hand copying the texts to add to her own library herself.” He said, knowing it would be a big job if the mages had an extensive library.

Akvin nodded, excused himself politely from the meeting, and strode out. He packed a light bag, dressed in his best black leather, and set off to seduce the Goddess of Memory and Writing to get what he wanted for his newest project. Lormar Tower was decidedly a pre-valterrian Alahea tower that used to reside on the boarder between the Suvan Empire and the Alahean Empire. Now, however, it had a nice coastal location overlooking the now inundated Suvan Sea. Akvin materialized outside of the tower’s entrance and strode up to it, knocking politely.

A stranger answered the door in the form of a lovely dark-haired woman with soft eyes. There were no guards and the tower itself didn’t seem to be teaming with people. It was, however, surrounded with gardens and livestock, with a expansive cattle yard and shelter that housed a milk cow and several precocial pigs. Chickens and geese expertly tended the garden, nibbling away at the pests that plagued such places even after The Valterrian. Akvin marveled at the thriving situation here, wondering if there was indeed hope for bigger populations like the Dyres and their kin.

“Can I help you?” The woman asked, curious but wary. Akvin put on his most charming smile, bowed low, and quietly asked. “I’m looking for a scholarly woman who might perhaps be here copying texts. I have no idea if she still is, but this was her last known location. She often goes by Laya. I’m Kultra, a friend of hers.” He said carefully, not sure if the residents in question would know of Qalaya’s true visage. The woman smiled, nodded, and was very helpful.

“Yes, Laya is here. It’s nice to meet you Kultra. I’m Nora Winters. Laya is upstairs in the library. Won’t you come in? I’ll show you to her.” The woman said politely, but with an edge to her gaze that told Akvin she knew exactly what she was dealing with. Akvin politely followed the woman inside the massive tower and immediately up the stairs that circled its inner walls to the third level where the library was. Nora left him at the doorway to the library after quietly knocking, swinging it open, and gesturing him inside.

Akvin made short work of the walk, quietly joining Qalaya where she was bent over a text. She glanced up, almost absent mindedly, and then did a double take and frowned. “What do you want?” She asked in a carefully neutral voice as Akvin sank down in a chair opposite of her and rested his hands on the table.

“This family… The Winters…. they are thriving. How did they do it?” He asked, glancing around, looking impressed at the condition of the tower, its library, and of its occupants. If all was as it appeared at face value, the humans were doing well for themselves. Qalaya smiled. She was truly a beautiful Goddess though her demeanor was that of a typical librarian, often stoic and expressionless.

“They are my followers. Gatherers of knowledge, they saved more books single handedly than most of the family groups combined. Their library helps them tremendously and that is why they are thriving. They even retain some of the pre-valterrian skills mortals had.” She said proudly, her smile dying on her lips as she looked him over. “Why are you here, Akvin?” She asked cautiously, eyeing his attire. Qalaya and Akvin Kultra didn’t know each other well. They didn’t roam in the same circles and rarely did their domains cross, though Qalaya kept track of Akvin’s inventions and creations.

“I need something from you.” He said, getting right to the point. “The Dyres are going to Surface and they are so woefully unprepared. Though their group is more than three hundred strong and overcrowding is an issue where they live beneath, they haven’t retained much skill and saved almost no books or writings from before. What they build, they will have to build with little or no knowledge. I doubt they’d even recognize a plow of they saw one, let alone a hoe or a rake for farming. I wish to help them. I’ve of a mind to craft something, a ring of power for them, but in order for it to work I need a drop of your blood.” He said frankly, knowing it was a lot to ask a fellow Deity. Their blood contained their power and even a mere drop of it could be a potent thing.

“Tell me of this ring and what it will do. And for that matter, why it will require my blood.” She said thoughtfully. Akvin felt it was a promising response. She hadn’t said no, and further questions were no issue.

“I wish to craft them a ring of creation, one that will manifest anything I know of from my memory that will help them solve a problem or do a task. I have enough power that I can sacrifice to its crafting to make sure the items can come unlimited for a time, but last only a single day… long enough for them to copy the items and make their own. Should they need to turn soil to plant, a plow would manifest, and their blacksmiths could reproduce it. I need your blood to translate my memories into the ring so it can produce the items. It will be almost sentient, a signet for the new leadership of what will grow from the Dyres family group. I foresee them going a long way and being a lasting force in the future, but only with a bit of help. It is a great favor you do for me and I will owe you one in exchange.” He said sincerely.

Qalaya nodded.

She extended her hand and offered the tip of her finger. “Just a drop. That should be enough of my power to do what you need.” She said and then added… “And a favor owed, naturally, and perhaps one I will collect soon.” She added, smiling at Him, knowing Akvin a grand crafter, probably one of the World’s greatest. A favored owed to Her by Him would not be a burden she’d carry long before she collected it.

He pulled a vial from his leather pants pocket, extracted a glittering dagger from his belt, and with the gentlest of touches nicked the end of her finger and collected her blood. After that, rather than departing rapidly to hurry back to craft his ring, he sat well into the night, visiting with Qalaya and getting to know her. In fact, on the whole, he stayed three days before he took his leave of Lormar Tower and returned to the caves The Dyres people inhabited.

Taking to his laboratory, he spent ten complete days crafting the ring. He turned it into a Signet for Tylin to wear, one Akvin hoped he’d pass down through the generations to the leaders of what would in later years become Sylira. And as for Qalaya. She called in her favor almost immediately. Shortly thereafter, Akvin vanished from the newly Surfaced colony of Sylira and wasn’t seen for ten years. When he returned, Lawrence was in power and the first stones of the Fortress of Sylira had been laid. Upon his hand, the signet ring of the Dyres family – The Ring of Creation – was still being worn.

Akvin Kultra was one such creature. The creative, innovative master inventor was passing time hanging with the riff raff off the coast of the new sea far beneath the surface. Ivak destroyed the world five centuries before and humanity was just now on the cusp of emerging like a grub from the soil they’d taken shelter in.

They had started small, sending adventurous types up and out onto the surface to explore and report. Later, hunting parties had gone forth and while some never returned, enough did with fresh meat and wild edibles that people started growing restless. The signs of Djed Storms had long been gone, though their memory still terrified the huddled masses. And so it was the leadership of the humans of the Dyres family gathered, made plans, and came to agree that it was time to at least partially surface.

“Are you sure it’s safe?” Tylin Dyres asked again, raising an eyebrow and glancing at Glav. The three of them were yet again having a meeting. Akvin was growing weary of meetings. He required action rather than the talk of action, so his leather clad knee was bouncing restlessly much like a deviant child. Glav gave him a look that included a raised eyebrow and the miscreant God shrugged. Unlike Glav, Akvin had his doubts these humans could survive the surface.

He wanted them too.

However, they simply had forgotten so much in their day to day living. His doubt was the reason Tylin was asking Glav and not Akvin. Akvin would have told him straight that he felt humanity to newly stupid to survive the surface since Ivak had robbed them of all their culture and hard-won advances in technology. Had more written work survived, then Humans would have had a fighting chance to make it on the surface. However, as things were saying Humans could survive was like trying to tell a person they could learn to cook without pots, pans, ingredients, recipes or even a fire.

Akvin knew it. Glav knew it. By Sylir’s pristine yet very dead balls, even The Goddess of Memory and Writing knew it. Akvin grumbled. He gave Glav a seething look. The son of Sylir hadn’t yet rose to replace Peace and probably couldn’t for some time to come. Certain things would have to happen first, namely Xhyvas making an appearance back to the land of living in order for them to pinpoint where they could rob enough divine to raise Glav’s power to that of Sylir’s former glory.

Until then, they would have to bide their time. Glav just chuckled at Akvin’s seething glance. He knew Akvin was restless and wanted to get the migration upwards underway, but he also knew that he didn’t want it to be an outright slaughter when the humans beneath faced the wildlife above.

“Its not going to be safe for a long long time. But if you are asking have the Djed Storms passed, yes… unless something else significant changes above, the abnormal weather has settled and you shouldn’t be facing those issues when you surface.” Glav assured him, knowing it to be true. He himself had consulted with Zulrav and the God of the Winds had indeed assured him that the wild djed had spent itself enough to stop effecting the weather and creating abnormal storms.

Tylin Dyres nodded, looked thoughtful, and sighed. “We’ll plan the ascent for the first of Spring. I can’t think of a better way to celebrate one more year of survival than to do it on the anniversary of The Valterrian.” He said thoughtfully. “Then we can see if we can get fields going, crops planted, and perhaps break ground on some sort of stronghold.” He said, tapping his chin and glancing around at his advisors.

Glav and Akvin nodded, though Glav was the only one truly focused on Tylin’s words. Akvin’s head was already miles away. He’d had an idea, and one that would require him to look up Qalaya’s location and ask a boon of Her. Akvin was a player who knew how to stack the decks. He was going to see if he couldn’t indeed ‘stack the deck’ for Tylin and his people before the deadline the human leader had just set for himself.

That meant finding Qalaya. Akvin glanced at Glav. When the others at the meeting were distracted with the business at hand and discussing things loudly, the Magecrafter leaned over and asked Glav a question. “Do you have any idea where Qalaya is? I just had an idea for something that might help Tylin and I need something from Her to do it.” He said, looking thoughtful. Glav shrugged. “She could be anywhere. Last I heard She was …. “ He seemed to reach inside himself, as if struggling for the memory. “Lormar Tower.” He said abruptly. “There were already surfaced mages there with a remnant library she was collecting.” Glav elaborated.

Akvin nodded. Glav had an excellent memory and an ear on the chatter the Gods carried out among themselves. If anyone knew where she was last seen, it would have been him. “Think shes still there?” He asked casually, already planning a trip.

Glav nodded. “I don’t see why not. She’s probably hand copying the texts to add to her own library herself.” He said, knowing it would be a big job if the mages had an extensive library.

Akvin nodded, excused himself politely from the meeting, and strode out. He packed a light bag, dressed in his best black leather, and set off to seduce the Goddess of Memory and Writing to get what he wanted for his newest project. Lormar Tower was decidedly a pre-valterrian Alahea tower that used to reside on the boarder between the Suvan Empire and the Alahean Empire. Now, however, it had a nice coastal location overlooking the now inundated Suvan Sea. Akvin materialized outside of the tower’s entrance and strode up to it, knocking politely.

A stranger answered the door in the form of a lovely dark-haired woman with soft eyes. There were no guards and the tower itself didn’t seem to be teaming with people. It was, however, surrounded with gardens and livestock, with a expansive cattle yard and shelter that housed a milk cow and several precocial pigs. Chickens and geese expertly tended the garden, nibbling away at the pests that plagued such places even after The Valterrian. Akvin marveled at the thriving situation here, wondering if there was indeed hope for bigger populations like the Dyres and their kin.

“Can I help you?” The woman asked, curious but wary. Akvin put on his most charming smile, bowed low, and quietly asked. “I’m looking for a scholarly woman who might perhaps be here copying texts. I have no idea if she still is, but this was her last known location. She often goes by Laya. I’m Kultra, a friend of hers.” He said carefully, not sure if the residents in question would know of Qalaya’s true visage. The woman smiled, nodded, and was very helpful.

“Yes, Laya is here. It’s nice to meet you Kultra. I’m Nora Winters. Laya is upstairs in the library. Won’t you come in? I’ll show you to her.” The woman said politely, but with an edge to her gaze that told Akvin she knew exactly what she was dealing with. Akvin politely followed the woman inside the massive tower and immediately up the stairs that circled its inner walls to the third level where the library was. Nora left him at the doorway to the library after quietly knocking, swinging it open, and gesturing him inside.

Akvin made short work of the walk, quietly joining Qalaya where she was bent over a text. She glanced up, almost absent mindedly, and then did a double take and frowned. “What do you want?” She asked in a carefully neutral voice as Akvin sank down in a chair opposite of her and rested his hands on the table.

“This family… The Winters…. they are thriving. How did they do it?” He asked, glancing around, looking impressed at the condition of the tower, its library, and of its occupants. If all was as it appeared at face value, the humans were doing well for themselves. Qalaya smiled. She was truly a beautiful Goddess though her demeanor was that of a typical librarian, often stoic and expressionless.

“They are my followers. Gatherers of knowledge, they saved more books single handedly than most of the family groups combined. Their library helps them tremendously and that is why they are thriving. They even retain some of the pre-valterrian skills mortals had.” She said proudly, her smile dying on her lips as she looked him over. “Why are you here, Akvin?” She asked cautiously, eyeing his attire. Qalaya and Akvin Kultra didn’t know each other well. They didn’t roam in the same circles and rarely did their domains cross, though Qalaya kept track of Akvin’s inventions and creations.

“I need something from you.” He said, getting right to the point. “The Dyres are going to Surface and they are so woefully unprepared. Though their group is more than three hundred strong and overcrowding is an issue where they live beneath, they haven’t retained much skill and saved almost no books or writings from before. What they build, they will have to build with little or no knowledge. I doubt they’d even recognize a plow of they saw one, let alone a hoe or a rake for farming. I wish to help them. I’ve of a mind to craft something, a ring of power for them, but in order for it to work I need a drop of your blood.” He said frankly, knowing it was a lot to ask a fellow Deity. Their blood contained their power and even a mere drop of it could be a potent thing.

“Tell me of this ring and what it will do. And for that matter, why it will require my blood.” She said thoughtfully. Akvin felt it was a promising response. She hadn’t said no, and further questions were no issue.

“I wish to craft them a ring of creation, one that will manifest anything I know of from my memory that will help them solve a problem or do a task. I have enough power that I can sacrifice to its crafting to make sure the items can come unlimited for a time, but last only a single day… long enough for them to copy the items and make their own. Should they need to turn soil to plant, a plow would manifest, and their blacksmiths could reproduce it. I need your blood to translate my memories into the ring so it can produce the items. It will be almost sentient, a signet for the new leadership of what will grow from the Dyres family group. I foresee them going a long way and being a lasting force in the future, but only with a bit of help. It is a great favor you do for me and I will owe you one in exchange.” He said sincerely.

Qalaya nodded.

She extended her hand and offered the tip of her finger. “Just a drop. That should be enough of my power to do what you need.” She said and then added… “And a favor owed, naturally, and perhaps one I will collect soon.” She added, smiling at Him, knowing Akvin a grand crafter, probably one of the World’s greatest. A favored owed to Her by Him would not be a burden she’d carry long before she collected it.

He pulled a vial from his leather pants pocket, extracted a glittering dagger from his belt, and with the gentlest of touches nicked the end of her finger and collected her blood. After that, rather than departing rapidly to hurry back to craft his ring, he sat well into the night, visiting with Qalaya and getting to know her. In fact, on the whole, he stayed three days before he took his leave of Lormar Tower and returned to the caves The Dyres people inhabited.

Taking to his laboratory, he spent ten complete days crafting the ring. He turned it into a Signet for Tylin to wear, one Akvin hoped he’d pass down through the generations to the leaders of what would in later years become Sylira. And as for Qalaya. She called in her favor almost immediately. Shortly thereafter, Akvin vanished from the newly Surfaced colony of Sylira and wasn’t seen for ten years. When he returned, Lawrence was in power and the first stones of the Fortress of Sylira had been laid. Upon his hand, the signet ring of the Dyres family – The Ring of Creation – was still being worn.

Whereabouts:

The Current Location & Ringbearer

Secret :

Unlike other Rings of Power, Akvin’s Ring of Creation has never been lost. Cleverly fashioned into a signet ring for the House of Dyres, The Ring of Creation has always graced the hand of The Lord of Syliras. Passed from Tylin to Lawrence, his adult son, the ring was then passed to each eldest son as they reached their prime and assumed the role of Grandmaster of the Syliran Knights and Leader of Syliras.

To this day, this lovely signet still graces Loren Dyres’ firm hand. Some say it is the reason for the Dyres family’s success and the fact that when so many others perished during The Surfacing, the Dyres family succeeded beautifully and went on to found the lovely city of Syliras and the noble order of Syliran Knights.

Akvin Kultra has been forever welcomed through the gates of Syliras and has always held a suite of rooms – always encompassing a magecrafting workshop – within the fortress of the city somewhere. Though he rarely stayed more than fifty years or so at a time, he was a frequent visitor and companion of both Glav Navik and assorted other Dieties that often call Syliras home.

To this day, this lovely signet still graces Loren Dyres’ firm hand. Some say it is the reason for the Dyres family’s success and the fact that when so many others perished during The Surfacing, the Dyres family succeeded beautifully and went on to found the lovely city of Syliras and the noble order of Syliran Knights.

Akvin Kultra has been forever welcomed through the gates of Syliras and has always held a suite of rooms – always encompassing a magecrafting workshop – within the fortress of the city somewhere. Though he rarely stayed more than fifty years or so at a time, he was a frequent visitor and companion of both Glav Navik and assorted other Dieties that often call Syliras home.

They laugh at me because I am different.

I laugh at them because they are all the same.

Painted Sky Jewelry (The Wildlands) | Crossroads Jewelry (The Outpost)

-

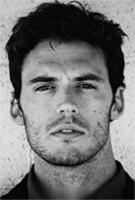

Kelski - Freedom is earned. Fight for it.

- Posts: 1598

- Words: 2015452

- Joined roleplay: July 3rd, 2014, 11:08 pm

- Location: The Wildlands of Sylira & The Empyreal Demesne

- Race: Kelvic

- Character sheet

- Storyteller secrets

- Plotnotes

- Medals: 11

-

-

-

-

-

Rings of Power Challenge Weekend (6, 7, 8)

![]() by Okara on July 9th, 2018, 3:28 am

by Okara on July 9th, 2018, 3:28 am

|

-

Okara - Great stories start with humble beginnings.

- Posts: 280

- Words: 218993

- Joined roleplay: May 30th, 2016, 12:34 am

- Location: Syka

- Race: Konti

- Character sheet

- Storyteller secrets

- Plotnotes

Rings of Power Challenge Weekend (6, 7, 8)

![]() by Tarn Alrenson on July 9th, 2018, 3:45 am

by Tarn Alrenson on July 9th, 2018, 3:45 am